Introduction

If you read Part 1 of this article, you would know that what we call the "tail gut" secures the violin tailpiece to the end pin (a.k.a. tail button). Part 1 ended with the assertion that the tail gut is more important than most musicians realize. Assuming a properly set-up violin or fiddle of at least moderate quality with decent strings and a good bow, NOTHING enhances (or diminishes) the sonority of a violin or fiddle than the adjustment of the tail gut and the material from which the tail gut is made!

A luthier rarely sees a traditional fiddle with a properly-adjusted tail gut. Generally, only violins and serious fiddlers who have routine maintenance done on their instruments have a properly-adjusted tail gut. We will get into what "properly-adjusted" really means later.

A Brief History of the Violin Tail Gut

Violin tail guts have not been made of "cat gut" (actually twisted strips of sheep intestine, just like "cat gut" violin strings) for a long time. The term "cat gut" was actually a joke (probably British); however, the joke status was lost over time…today, the average person believes that cats are actually butchered to make gut violin strings. It is actually sheep that are butchered, if that provides any peace-of-mind.

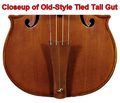

Tail guts of twine saturated with varnish or resin were also used; however, genuine gut continued to be favored. Tail guts, regardless of their composition, were tied to the tailpieces of Baroque and Modern violins for centuries, as shown in the photos of an early Modern violin below.

Click on the thumbnail images for larger views.

The loop (hidden from view in the photos) is attached to the end pin. These early tail guts stretched substantially during the "break-in" period and had to be re-tied frequently until they stabilized. Of course "stabilized" is a relative term, as humidity and temperature variations affects the early tail guts in the the same way that gut strings are affected.

Modern Tail Guts

The adjustable Nylon tail gut was invented in the 20th Century. Its invention is usually attributed to Frank Passa, who introduced the Sacconi brand tail gut. Wittneralso sells a similar adjustable nylon tail gut. Genuine Sacconi or Wittner tail guts are probably the most prevalent tail guts in use today. One hears many cautions about the poor quality of Asian imitations of the Sacconis and Wittners.

The modern nylon tail guts are threaded at their ends and are attached to a modern tailpiece with adjustment screws (see the photo below). They stretch a lot during break-in, requiring readjustment.

Metal Tail Guts

There have been other makers of metal tail guts; however, two German companies, Wittner and Infeld-Thomastik, both make excellent stainless steel tail guts. The metal ones tend to be called "tail hangers" or "tail wires". Stainless steel tail guts are VERY thin, but do not stretch much at all. The photo below shows a Wittner stainless steel tail gut on one of our Mountaineer Backpacker Fiddles.

Some musicians and luthiers claim that stainless steel tail guts improve the sound of an instrument and some claim that they make no difference or even detract from the sound. Our experience is that it depends on the instrument. Meanwhile, metal vs. Nylon is a popular argument topic in online discussion forums.

We use a Wittner stainless steel tail wire whenever we install a Tailpiece-Chin Rest Combo on a fiddle, generally one of our backpacker or travel instruments. The stiffness of stainless steel cable under tension helps to keep the chin rest part of the tailpiece-chin rest combo from rocking laterally.

The Kevlar Tail Cord

Tail cords made of braided Kevlar have appeared on the scene. These new tail guts, like all violin and fiddle accessories, are the topic of much debate. As with stainless steel tail wires, there are varying opinions about whether or not a Kevlar tail cord improves the sound of an instrument.

I suspect that if one has a very good instrument with an excellent setup, the composition of the tail gut is not going to make much of a difference in the instrument's sound quality. The average fiddle is a different story. Our experience is that the improvement in overall sonority on metal-strung fiddles is dramatic with a Kevlar tail cord. For many reasons, particularly the use of lower bridges, the g and d' strings of fiddles are not as responsive as one would desire. Use of Kevlar tail cords has always added significant power to the g and d' strings on the fiddles we have worked on.

This begs the question, is a Kevlar tail cord worth the trouble? We will re-visit this question.

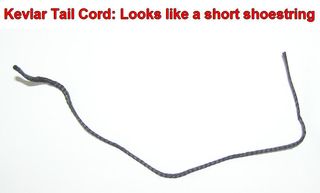

A Kevlar tail cord looks like a short length of waxed dress shoe string. We get ours from Dov Schmidt. See the photos below.

As will be shown in photos that follow, a Kevlar tail cord is tied to the tailpiece, just as gut or twine tail guts were tied to the tailpieces of Baroque violins. The knot (actually two knots) are NOT the same as the knot used on Baroque violins.

A compaint often heard about Kevlar tail cords is that is extremely difficult to tie the knots so that the tailpiece is the desired distance from the saddle AND the string "after-length" (the string length between the tailpiece and the bridge) is correct. The whole matter of the correct string after-length is a matter of constant debate.

The traditional first rule-of-thumb is that the string after-length should be approximately 1/6 of the playable string length. The second traditional rule-of-thumb is that the note emitted by plucking the strings between the bridge and the tailpiece should be as close as possible to 2 octaves + a 5th than plucking the playable string sections. These rules-of-thumb work fairly well with plain gut strings. The "rules" do not quite work out for modern strings with silk windings at the string ends, so a popular practice for steel or synthetic strings is about 55mm as a starting point, and then experimenting until optimal instrument sonority is achieved. There are all sorts of methods used by luthiers for determining when the optimal contribution of sonority of the tailpiece adjustment has been achieved, including tap-tuning the fingerboard and tailpiece so that the tap tones are equal. While we have the electronic equipment for tap-tuning (for tops, bass bars. etc.), we use our ears when adjusting a tailpiece.

With a Nylon or stainless steel adjustable tail gut, getting the optimal after-length adjustment on the tailpiece is no cake walk. Achieving the correct adjustment is diabolically difficult with a Kevlar tail cord. See the task description and accompanying photos in Part 3 of this article.

Leave a comment